In C++ trivial has a very specific meaning. Let’s look at examples of when being trivial can matter.

tl;dr

Read this if you just want the meat of the article.

Copying is expensive and can be avoided in many ways, with pointers or passing by reference. But there are use cases where copying is necessary or can be better (based on usage).

Do you have a class that stores data that you copy around a lot? Is that class not trivially-copyable? Try to make it so. There are some performance benefits in doing that.

Preamble

Sometimes you just need to sit down and write about your latest obsession. I did two short talks about it, and now it’s time to write it down and hopefully get it out of my system.

In this article I am focusing on when expensive objects are copied. There are multitudes of other ways to avoid copying and if you are able to, then do it.

Overview

There is a little side project I’ve been working with off and on over the past few years. In this project I needed to create a struct that was composed of a collection of other structs. It looked something like this.

struct Thing

{

Thing() = default;

// A handful of constructors

// ...

void SomeModifyingFunc();

// A handful of similar functions

// ...

std::vector<OtherThing> myOtherThings;

// A handful of similar member variables

// ...

};

The type OtherThing looks very similar to the type Thing. It’s Things all the way down!

I would then take an instance of this type, give it to a thread, it would do some work and give back a result. This type was completely standalone, so this was very easy to parallelize.

When I was doing performance analysis on the system, I saw that a lot of my time was spent on calling all sorts of constructors and allocating memory.

I started to investigate and to read more about how to avoid many of the allocations I was doing. I was already calling reserve() and I tried to reuse already allocated objects when possible.

But then I thought: “The sizes are always the same. I know them at compile time. So I can replace all the std::vector<> with std::array<>”

I wasn’t expecting any kind of performance boost by doing that, but when I ran the tests again I saw a boost, but only in one location.

The code looked something like this. It wasn’t integers but for our purposes it can be.

Compiler Explorer

struct MiniThing

{

MiniThing(): myIntA(0), myIntB(0){}

MiniThing(int aIntA, int aIntB)

: myIntA(aIntA), myIntB(aIntB){}

int myIntA;

int myIntB;

};

struct MiniThings

{

MiniThings() = default;

// used to be std::vector<MiniThing>;

std::array<MiniThing, 6> myMiniThings;

};

Why was replacing a std::vector<> with std::array<> giving a performance boost? They’re basically the same thing when you arrive at the memory location.

I wasn’t getting a boost in iterating through the elements, that bit of code was minimal anyway. I was getting a boost in copying MiniThings around.

After throwing a code snippet into Compiler Explorer I saw what was going on.

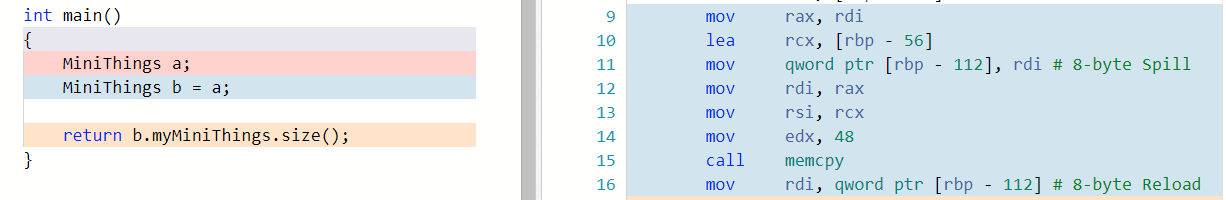

This is the version with std::array<>, here you can see the assembly and the blue line where a call to memcpy is generated.

This is the version with std::vector<>, here you can see again the blue line but no call to memcpy but a call to the copy constructor of MiniThings.

Trivial

To quote cppreference.

“Objects of trivially-copyable types are the only C++ objects that may be safely copied with std::memcpy”

So what does it mean to be trivially-copyable? (emphasis mine)

Requirements

- Every copy constructor is trivial or deleted

- Every move constructor is trivial or deleted

- Every copy assignment operator is trivial or deleted

- Every move assignment operator is trivial or deleted

- at least one copy constructor, move constructor, copy assignment operator, or move assignment operator is non-deleted

- Trivial non-deleted destructor

- This implies that the class has no virtual functions or virtual base classes.

Scalar types and arrays of TriviallyCopyable objects are TriviallyCopyable as well, as well as the const-qualified (but not volatile-qualified) versions of such types.

Here the word trivial does not take on the English language meaning, rather it means that the constructor or assignment operator is not implemented by the user. It has a few other meanings but this will suffice for now.

The reasoning is that as soon as you implement a Copy Constructor, it needs to be called when you copy, no matter how it’s implemented.

There exists a few <type_traits> checks that you can use to make sure the class you are defining behave in the manner you expect. Here is what I added to all the classes I needed to be trivially-copyable.

Compiler Explorer

#include <type_traits>

struct MiniThings

{

MiniThings() = default;

std::array<MiniThing, 6> myMiniThings;

};

static_assert(std::is_trivially_copyable_v<MiniThings>, "Some Msg");

So if by accident you make your class no longer trivially copyable, it will not compile. How handy.

When talked to people about Trivially-Copyable I would sometimes get replies like “Oh, it’s only because the type is an aggregate”.

Being a POD type, being an Aggregate and being Trivially-Copyable are not interchangeable, though they can overlap.

Compiler Explorer

struct NotAggregate

{

NotAggregate() = default;

NotAggregate(int aX): x(aX){}

int x;

};

static_assert(!std::is_aggregate_v<NotAggregate>);

static_assert(std::is_trivially_copyable_v<NotAggregate>);

static_assert(std::is_pod_v<NotAggregate>);

struct NotAggregateOrPOD

{

NotAggregateOrPOD(){};

int x;

};

static_assert(!std::is_aggregate_v<NotAggregateOrPOD>);

static_assert(std::is_trivially_copyable_v<NotAggregateOrPOD>);

static_assert(!std::is_pod_v<NotAggregateOrPOD>);

Testing

But how much of a difference can this make?

I wanted to create a scenario where I could compare a few classes to each other.

One thing that sprang to mind immediately was doing a large MySQL query. So I added 500.000 “users” to a database.

Each row was a user and had:

- account_id (guid, 36 character)

- company_id (guid, 36 characters)

- email (around 10-20 characters, field was 255 max)

- password hash (64 character hash)

I used a MySQL C library to fetch each row into a vector. So I would have a std::vector<User> of length 500.000. But this query is not the thing I wanted to time.

I wanted to time a copy of this vector into another vector.

To prevent excessive optimization since I didn’t use the vector after it being copied, I saved the size of the copied vector into a global volatile value, which seemed to work just fine and kept giving me consistent results.

I timed the copy 10.200 times and saved it to a file. I removed the slowest 100 and fastest 100 because I was getting two or three timings that seemed out of the ordinary. (like 3-4 seconds)

I used clang 6.0.1 on a Fedora 28 distro. The test was compiled with clang++ -O3 -std=c++2a

Compiler Explorer (more code on CE than shown)

static volatile uint32_t preventOpt = 0;

for(int i = 0; i < 10200; ++i)

{

// Simple class that

// calls high_resolution_clock::now()

// on construction and destruction

// and prints the diff

ScopeDuration d;

std::vector<User> users_copy = users;

preventOpt = users_copy.size();

}

This copy was done for each class I defined.

Since MySQL needs memory already allocated to write to, and if you create a string it will be empty by default. So I only used one instance of the class for MySQL to write to and called resize() on the strings so they were of the same size as the arrays. This class was then push_back() into the vector and reused for the next query.

To make sure I was getting back the data that was in the database, I had a simple validation function to check the values of a couple of rows to make sure I didn’t get any empty strings or corrupted values.

As stated before, I did not time the MySQL fetch operations, just the copy that happened afterwards.

Here are the classes I made and tested.

Compiler Explorer

// std::array, everything default

// both aggregate and trivially-copyable

struct UserArrayDefault

{

std::array<char, 36> myAccountId;

std::array<char, 36> myCompanyId;

std::array<char, 255> myEmail;

std::array<char, 64> myPasswordHash;

};

static_assert(std::is_aggregate_v<UserArrayDefault>);

static_assert(std::is_trivially_copyable_v<UserArrayDefault>);

// std::array, user implemented default constructor

// trivially-copyable but not aggregate

struct UserArrayDefaultConstructor

{

UserArrayDefaultConstructor(){};

std::array<char, 36> myAccountId;

std::array<char, 36> myCompanyId;

std::array<char, 255> myEmail;

std::array<char, 64> myPasswordHash;

};

static_assert(!std::is_aggregate_v<UserArrayDefaultConstructor>);

static_assert(std::is_trivially_copyable_v<UserArrayDefaultConstructor>);

// std::array, user implemented default and copy constructors

// not trivially-copyable and not aggregate

struct UserArrayCopyConstructor

{

UserArrayCopyConstructor(){};

UserArrayCopyConstructor(const UserArrayCopyConstructor& aUnt)

: myAccountId(aUnt.myAccountId)

, myCompanyId(aUnt.myCompanyId)

, myEmail(aUnt.myEmail)

, myPasswordHash(aUnt.myPasswordHash){}

std::array<char, 36> myAccountId;

std::array<char, 36> myCompanyId;

std::array<char, 255> myEmail;

std::array<char, 64> myPasswordHash;

};

static_assert(!std::is_aggregate_v<UserArrayCopyConstructor>);

static_assert(!std::is_trivially_copyable_v<UserArrayCopyConstructor>);

// std::string, everything default

// aggregate but not trivially-copyable

struct UserStringDefault

{

std::string myAccountId;

std::string myCompanyId;

std::string myEmail;

std::string myPasswordHash;

};

static_assert(std::is_aggregate_v<UserStringDefault>);

static_assert(!std::is_trivially_copyable_v<UserStringDefault>);

// std::string, user implemented default constructor

// not trivially-copyable and not aggregate

struct UserStringDefaultConstructor

{

UserStringDefaultConstructor(){};

std::string myAccountId;

std::string myCompanyId;

std::string myEmail;

std::string myPasswordHash;

};

static_assert(!std::is_aggregate_v<UserStringDefaultConstructor>);

static_assert(!std::is_trivially_copyable_v<UserStringDefaultConstructor>);

// std::string, user implemented default and copy constructors

// not trivially-copyable and not aggregate

struct UserStringCopyConstructor

{

UserStringCopyConstructor(){};

UserStringCopyConstructor(const UserStringCopyConstructor& aUnt)

: myAccountId(aUnt.myAccountId)

, myCompanyId(aUnt.myCompanyId)

, myEmail(aUnt.myEmail)

, myPasswordHash(aUnt.myPasswordHash){}

std::string myAccountId;

std::string myCompanyId;

std::string myEmail;

std::string myPasswordHash;

};

static_assert(!std::is_aggregate_v<UserStringCopyConstructor>);

static_assert(!std::is_trivially_copyable_v<UserStringCopyConstructor>);

Results

Here are the graphs for all the classes. 10.000 copies each timed individually.

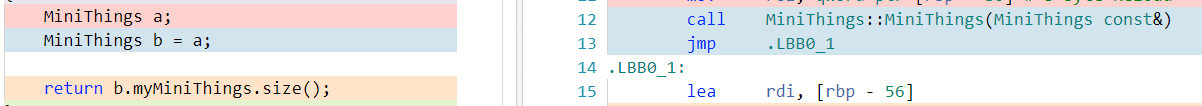

Array - All Default Constructors

This one is sitting nicely between 0.116 and 0.138 seconds. With a mean of 0.12628 and median of 0.123.

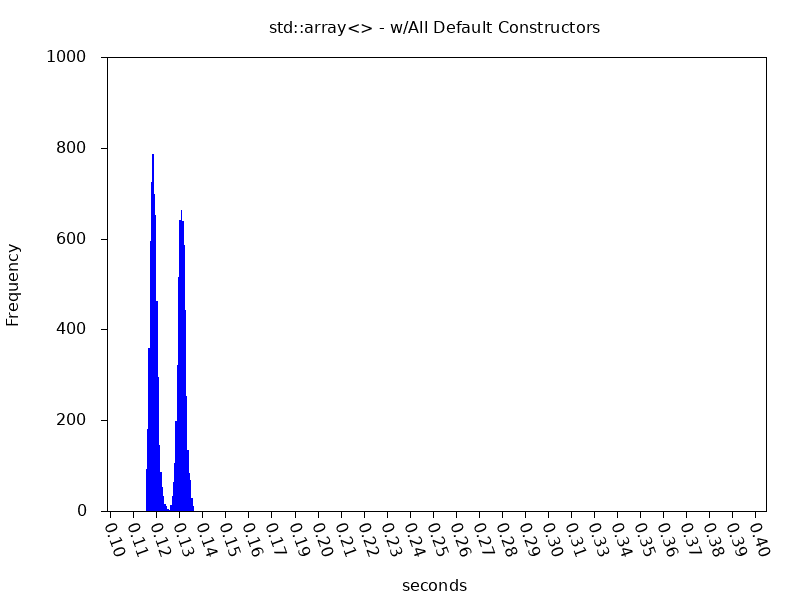

Array - User Defined Default Constructor

Here is an increase to 0.141 and 0.166 seconds, by just defining the default constructor. Mean of 0.15311 and median of 0.15692.

Array - User Defined Copy Constructor

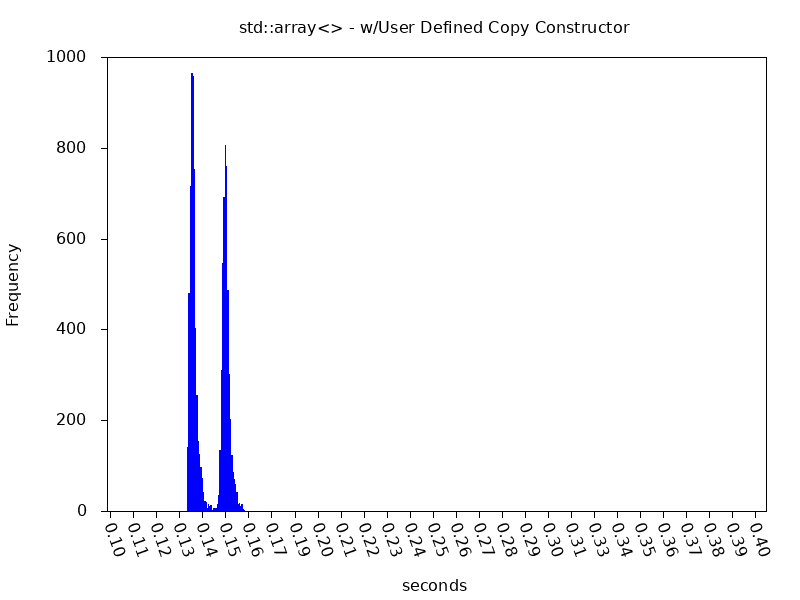

A bit different band but still sitting around similar values as the previous one, of 0.135 and 0.158. Mean of 0.1457 and median of 0.14185.

String - All Default Constructors

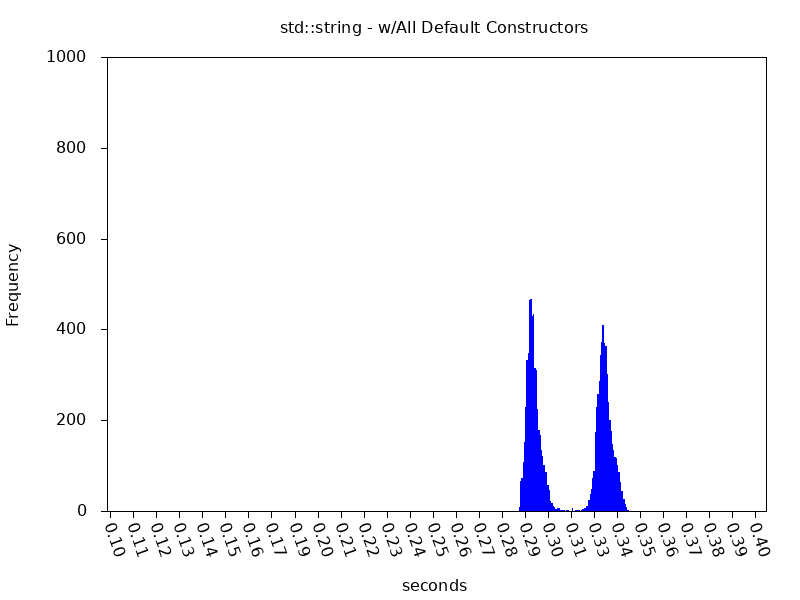

A huge increase from the array classes. 0.29 to 0.34 seconds. Mean of 0.3131 and median of 0.3068.

String - User Defined Default Constructor

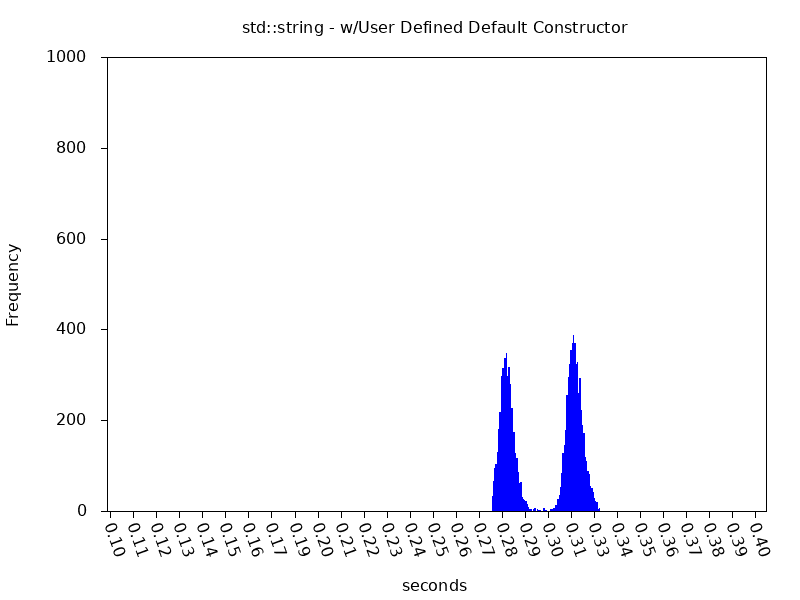

Slightly faster than previous one, but still around the same values. 0.277 to 0.327. Mean of 0.30165 and median of 0.31122.

String - User Defined Copy Constructor

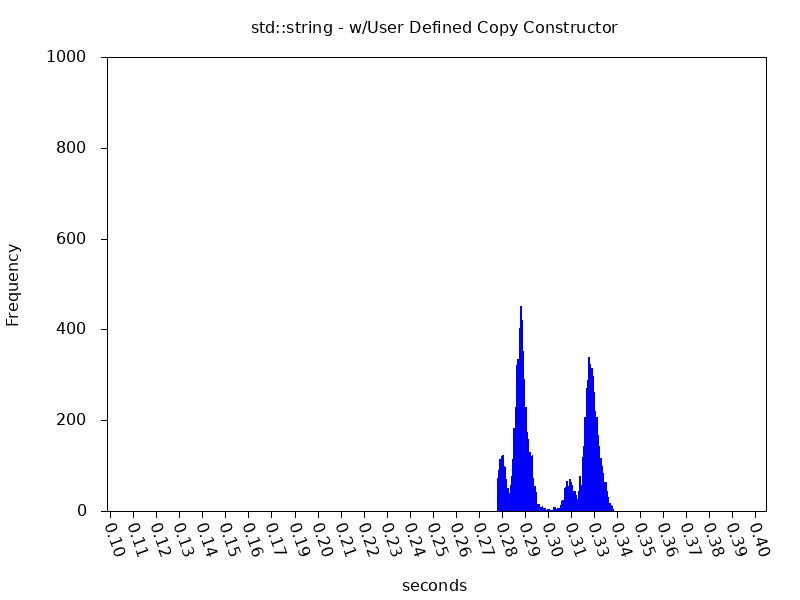

A mix of the two. A little rougher of a graph but sitting on the 0.28 to 0.33 band. Mean of 0.3051 and median of 0.2961.

All graphs in one

Here they are all together, slightly colored to try to separate them apart.

- Red is All Default Constructors, no user defined

- Blue is User Defined Default Constructor, no copy constructor

- Purple is User Defined Copy and Default Constructors

The main thing to note is how significantly faster the All Default Constructors in the std::array<> case is while in the std::string case they are all huddled together with User Defined Default Constructor a bit faster.

Note that I did run tests on using std::vector<> instead of std::string as well. Using vectors gave very similar numbers to the std::string classes.

If you had the same setup as this test but were using a class with std::array<> members and removed all constructors you had written you would see an improvement of 17.5% ((0.15311 - 0.12628) / 0.15311) * 100)

If you had the same setup as this test but were using a class with std::array<> instead of a class of std::string you would see an improvement of 59.6% ((0.3131 - 0.12628) / 0.3131) * 100)

What’s with the two humps?

So this stumped me for a while. We are getting a bimodal distribution when running these tests. Why?

I asked Twitter about this. Scott Wardle and Staffan Tjernström suggested that it was due to caching. Specifically that I was sometimes hitting 2 cache lines and sometimes not.

To test this I ran some tests again but instead of having all 4 class members, I reduced them down to 2.

This was promising. When I hit cache on both members, I would get the smaller hump on the left, when I would hit one and not the other, I would get the big bump, which has double the likelihood of happening.

Then I reduced it down to one member.

Only one hump with a tail. So that is highly suggestive that this is the reason.

Conclusion

Only two of the classes tested were trivially-copyable. Array All Default Constructors and Array User Defined Default Constructor.

Array All Default performed the best. The User Defined Default Constructor performed the worst of the std::array<> classes. So there seems to be something more to this, or that the band is already too narrow to make a significant difference.

All the std::string classes, performed significantly worse than std::array<> and had little correlation in what constructors they defined. At least none that I could easily see.

It seems that if the all the types in your class are already trivially-copyable you will see some improvements in making sure the class itself trivially-copyable also, but if the types are not trivially copyable themselves, as is in the std::string case, you will see no significant difference.

And if you are able to convert your class members into types that are trivially-copyable, you will see a large benefit.