Regression done quick!

What is Blogvent? (tl;dr I am going to write one post a day for all of December as a way to practice writing.)

Origins

A couple of years ago Jason Turner looked into porting Doom (or some of it) to C++. He did several livestreams of his efforts and it then resulted in this GitHub repo.

Then Patricia Aas has the idea to use Doom as the target in a security training she was working on. She even found and fixed a possible exploit in the game that was then patched in the Chocolate Doom source port.

Hearing that Patricia was working on Doom stuff got me very interested, there was a lot to be done (and still is) so I wanted to find out where I could help out the most.

Moving fast and breaking Doom

When porting a entire video game over to a new language, you might break things. So we needed a nice way to make sure that whatever we did the game would still be playable.

Playing the game after each pull request is possible but what if you broke something more subtle? So we needed some automated tests to help us out with this. Unsurprisingly a video game from the 90s written in C does not come with a full suite of unit tests. But there is still hope.

Determined to test

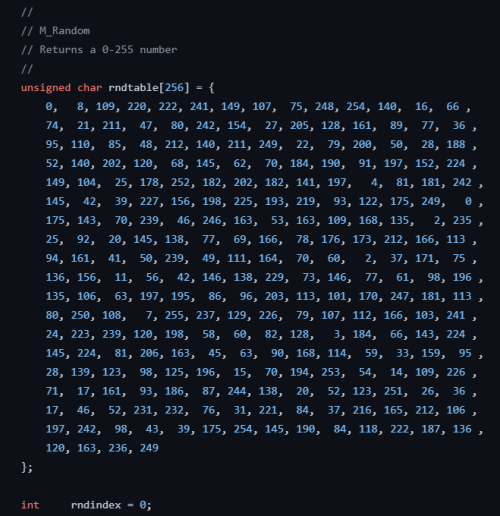

There is one property of Doom that is very useful to us. The randomness in the game is fully deterministic. It’s an array of random numbers and anytime anything in the game wants some randomness it is pulled from this array and the index is incremented.

The game is also single threaded, so given the same user inputs, the game always reacts in the same way. So you can save those user inputs into a small file and play it back.

This a well known feature in the game and is how people used to share cool moments between each other, and then was used in the speed running community to share fast completion times when internet speeds weren’t the best.

We can use this

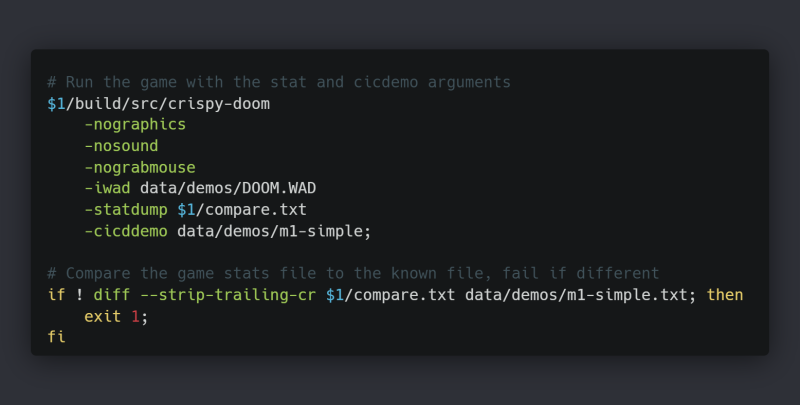

There is another feature of the game, the score screen. After the level is complete, the statistics are collected to show you how you did. The time, how many enemies kill, how many secrets found, etc. This can also be collected to a file.

We can combine these two features, the demo playback and the statistics feature to create a baseline. So I collected a series of demos and statistics outputs from a known good version of Doom. Now we just need to compare those results to our game and we should be good. Right?

Time, sweet time

Well this will still take time to run. So we need to fix that.

So I changed the game so given certain new command line inputs the game will run without needing to render anything to the screen and will run as fast as possible. This allowed us to run Doom in the command line against all the known tests.

Then what we had on our hands are regression tests we could execute to make sure we haven’t broken anything.

The hub

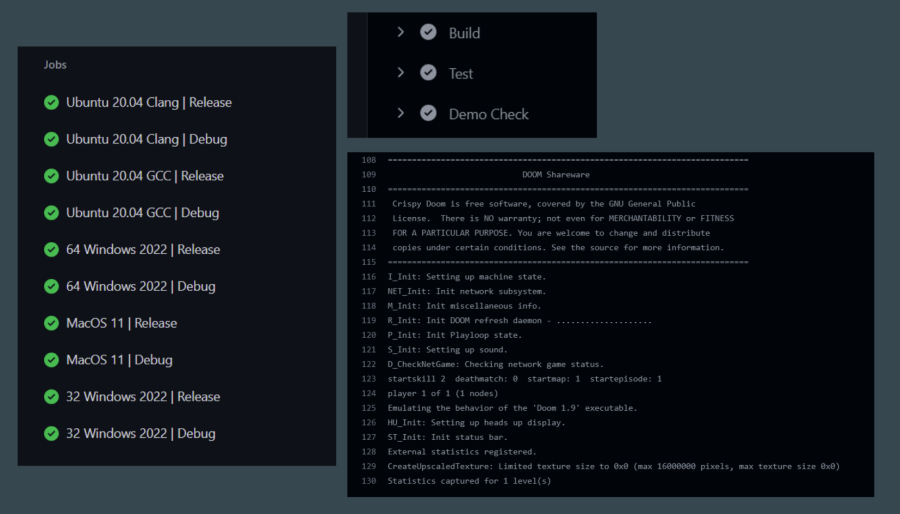

Where is a good place to run tests? In the CI/CD pipeline of our GitHub repository of course.

So that is what we have, after every PR a series regression tests is run to make sure we haven’t broken the game.

Then we can say “Doom runs on GitHub.”

This isn’t foolproof though. I’ve been trying to collect normal gameplay demos and also find demos that demonstrate strange engine behavior. So I asked the speed running community for resources (which they had a lot of) and this is where I’ve been pulling some of the demos from.

There is the Odd Demos Archive and the Compet-N/Speed Demos Archive I’ve been using. But we can’t use all of them since we can only run the Shareware version of the game on GitHub (due to copyright of course).